February 21, 2025

By Andrew Fink, Ph.D., Exovera Senior Russia Analyst

Sources withheld. Please contact us to obtain the source list.

The Russian mobile ground-based, anti-space, laser weapon Peresvet is usually described in Western literature as a weapon to counter photoreconnaissance satellites. It is generally accepted that the Peresvet is designed to blind photoreconnaissance satellite sensors by either flooding them with photons (possibly damaging or destroying the sensors), or by triggering shutters or other countermeasures on any targeted satellite which protect its sensors from damage – achieving a mission-kill and preventing the satellite from using its sensors while it is under the Peresvet’s attack. This is likely one mission of the Peresvet, and some Russian messaging reinforces this.

The Russian mobile ground-based, anti-space, laser weapon Peresvet is usually described in Western literature as a weapon to counter photoreconnaissance satellites. It is generally accepted that the Peresvet is designed to blind photoreconnaissance satellite sensors by either flooding them with photons (possibly damaging or destroying the sensors), or by triggering shutters or other countermeasures on any targeted satellite which protect its sensors from damage – achieving a mission-kill and preventing the satellite from using its sensors while it is under the Peresvet’s attack. This is likely one mission of the Peresvet, and some Russian messaging reinforces this.

However, the Peresvet’s primary mission is likely to defeat U.S. missile defense systems by dazzling low-Earth orbit infrared early-warning satellites linked to missile defense systems.

The currently envisioned architecture for a future U.S. national missile defense relies on these kinds of satellites to cue missile defense systems and track targets before they can be picked up on radars. As the U.S. begins planning for a more robust homeland missile defense system, analysts should take another look at the Peresvet and how Russia could use it to neutralize future missile defenses.

In his new executive order (EO) “The Iron Dome for America”, President Trump ambitiously ordered the development of an aerospace defense system that could defend against “any foreign aerial attack on the homeland”, as opposed to a more limited National Missile Defense (NMD) system designed to “stay ahead of rogue-nation threats and accidental or unauthorized missile launches.” This EO directed the Secretary of Defense to submit plans for a number of systems for a “next-generation missile defense shield”, including space-based interceptors capable of boost-phase intercepts, terminal-phase interceptors, non-kinetic missile defeat capabilities, and the “Acceleration of the deployment of the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor layer” (HBTSS).

The HBTSS is the latest version of the low-earth-orbit IR sensor capability for missile defense. The Peresvet’s stated capabilities, the development history of the Peresvet and similar Russian laser weapons, and the circumstances surrounding its unveiling all suggest that the Peresvet is a threat to the HBTSS.

First, there is the Peresvet’s reported range, which is usually stated as 1,500 km (though one report places it at 500 km and another at 1,100 km). If its range is indeed 1,500 km, then the Peresvet far outranges photoreconnaissance satellites, which typically orbit at altitudes between 140 and 250 km. HBTSS satellites orbit at approximately 1,200 km, within the declared range of the Peresvet. The planned predecessor system of the HBTSS, the Space Tracking and Surveillance System (STSS), also had its satellites at an orbit of around 1,350 km, also within Peresvet’s reported range.

A possible objection to this line of argument based on the Peresvet’s reported capabilities is that they are merely reported capabilities. Russian journalists and officials could be deliberately inflating the range of their marvelous new mobile laser for propagandistic effect. This may be the case, but the idea that the Peresvet is targeted against HBTSS and other infrared satellites is also suggested by the Peresvet’s technological predecessor: the Russian Mobile Laser Technology Complex – 50 (MLTK-50). This was a Russian mobile CO2 laser developed for Gazprom in the 1990s, based on the Soviet Omega-2 CO2 experimental anti-aircraft laser.

The MLTK-50 was designed for demolition work, to allow Gazprom to remotely dismantle structures that were too dangerous to approach, such as a drilling rig that has collapsed around a raging fire at a natural gas wellhead. One Russian journalist wrote that the MLTK-50 was just the Omega-2 laser without the targeting system.

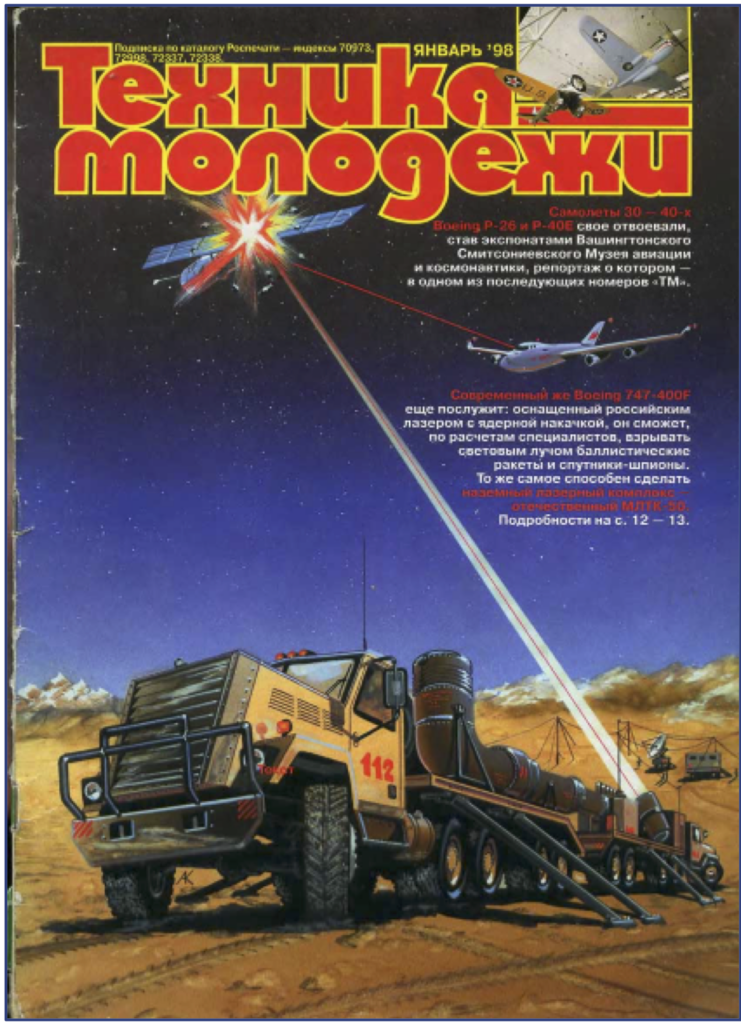

While the MLTK-50 was marketed as a civilian laser system, there were always hints that it could be used against satellites. Take, for example, this image from the Russian youth-oriented magazine, which depicts the MLTK-50 attacking a satellite (and might be considered the first public illustration of what would become the Peresvet).

CO2 lasers like the one used on the MLTK-50 emit photons along the infrared spectrum, making them ideal for lasers that could dazzle infrared-sensors. It is entirely possible that the Peresvet system has several lasers, lower-powered ones designed for targeting photoreconnaissance satellites as well as a primary, more powerful CO2 laser for attacking early warning satellites.

There are a limited number of images of the MLTK-50, but the few that do exist show a similarity to the likely core of the Peresvet laser system: a truck-based laser on at least two trailers.

Image of the MLTK-50

The Peresvet on the move

Another objection to the interpretation that the Peresvet is for use against the HBTSS is that the Peresvet was developed long before the HBTSS. The first suggestion of the Peresvet’s development in public Russian contract data was in 2012, when the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) issued a contract for developing “a mobile complex for suppressing optical-electronic reconnaissance and dual-use Earth remote sensing spacecraft for the needs of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation in 2012-2013.” According to a Russian press report, the Peresvet passed state tests around 2015, years before the HBTSS was even in development.

The Peresvet was probably not designed specifically to attack the HBTSS, but rather is the latest public Russian weapon designed to combat low-earth orbit missile defense IR sensors. In general, U.S. commentary on missile defense tends to focus on the kinetic bits, the kill vehicles that destroy missiles, or on the large expensive missile defense radars. The main ways to counter missile defenses that are considered publicly tend to be either the missiles themselves – ones that fly too fast or too low or maneuver to be countered by currently-envisioned systems – or by overwhelming any system with sheer numbers or with decoys.

Russian thought about how to counter U.S. missile defenses tends to focus more on the more vulnerable space-based sensors that have always been part of any envisioned national missile defense architecture since at least 2002. The immediate predecessor to the HBTSS was the Space-Based Infrared System Low (SBIRS-Low), later known as the STSS, a planned constellation of 30 low-earth orbit satellites. When the U.S. pulled out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty in 2002, one of Russia’s first public moves was to begin development of the Sokol-Echelon airborne laser dazzling system that targeted infrared sensors.

Russia cancelled the Sokol-Echelon laser system in 2011, around the time it was becoming clear that the STSS would remain as an experimental system with just two satellites in orbit, and about a year before the Russian MoD probably began the development of the Peresvet. However, just as the Peresvet did not come out of nowhere, neither did the HBTSS. Funding for the development of the HBTSS prototype first publicly appeared in late 2017, and by early 2018 it was clear that this new system would be the successor to the STSS.

The public unveiling of the Peresvet took place in March 2018 during a speech by Vladimir Putin to the Russian Federal Assembly. The part of this speech that focused on new strategic weapons was probably a direct response to the U.S.’s plans for a beefed-up missile defense system, including the planned development of the HBTSS.

Alongside the Peresvet, Putin also touted the Sarmat, Russia’s new super-heavy ICBM; the Avangard, Russia’s silo-based intercontinental hypersonic missile; the Kinzhal, an air-launched hypersonic missile; and the Poseidon, an intercontinental torpedo carrying a nuclear payload. All these other weapons were portrayed in this speech as means of countering any U.S. missile defense system. Why should the Peresvet be seen as the sole exception?

Finally, the Peresvet’s initial deployment suggests that it is designed to directly support Russia’s strategic rocket forces, rather than merely counter photoreconnaissance. Russian defense bloggers have identified five sites where the Peresvet was initially deployed, partially based on the construction of distinctive buildings that appear to be associated with the Peresvet and partly on public Russian contracts connected to the construction of these special sites. All of them are at the locations of Russian strategic rocket units that use the Yars mobile ICBM.

A system designed to defeat photoreconnaissance would likely first be deployed to protect leadership sites and command-and-control units, rather than mobile missile units. One of the Peresvet’s missions might be to blind US photoreconnaissance while these mobile Yars ICBMs are maneuvering to deploy out of their base during a crisis. However, blinding photoreconnaissance satellites while they are over a certain area might give important clues about the location of potential targets that can be sought by other means, such as through synthetic aperture radar satellites or drones. If, on the other hand, the ground-based Peresvet’s primary mission is to strike the HBTSS satellites that would be able to view and track the launch of these ICBMs, then they would probably want to be as close as possible to the actual launch sites in order to blind the satellites that are over the horizon and have a line of sight to the launches.

Analysts should seriously examine the potential threat of the Peresvet to the HBTSS or other space-based infrared sensors linked to missile defense. There is also the danger that the Peresvet, or something like it, could be proliferated to other states, such as Russia’s military allies of Iran and North Korea. Any missile defense plans aimed against near-peer adversaries need to take near-peer technology into account; otherwise, the U.S. may be in danger of building a larger version of a missile defense system adequate for limited rogue-state attacks, not the robust system called for in President Trump’s new Executive Order.